Caitlyn Liu

History of Modern and Contemporary Art

April 21, 2025

History of Modern and Contemporary Art

April 21, 2025

Windows into the Sacred and the Speculative

Across time and geography, Betye Saar’s Window of Ancient Sirens (1979) and the illuminated page Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves (ca. 1440) epitomize how material culture can be used to navigate spirituality, social identity, and personal memory. While these works stem from radically differing contexts, one medieval and European, the other modern and diasporic, they both engage with the archive, a practice of remembering and reimagining identity through symbolic vocabularies that encode memory, ancestry, and spiritual belief. Through distinct material approaches, both Saar and the Master of Catherine of Cleves construct visual systems that frame sacred figures and their identities, lineages, and cosmologies.

The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, produced in Utrecht by the anonymous Master of Catherine of Cleves, is a Book of Hours—a private prayer book that provided structured devotional rituals for elite laypeople. The inauguration page, Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child, focuses on the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child in a gold mandorla, housed in a towering Gothic-like altar. Both dressed in lapis-colored robes, their sanctity is represented through symmetry and divine elevation. Below, the patron, Catherine, appears in the left exterior of the altar, kneeling in reverence, holding her own Book of Hours. Directly beneath the Virgin is a coat of arms, combining the symbols of Catherine’s natal house of Cleves and her marital house of Guelders. The owl and rooster in the margins further amplify the page’s spiritual ecosystem: the owl as a guardian of divine wisdom, and the rooster as a call to vigilance and rebirth. Though Catherine is not physically centered in composition, her vivid red robe and forward position emphasize her centrality. Furthermore, the margins expand outward in naturalistic lines and patterns, establishing the page as a visual record of Catherine’s family and faith. As noted by The Morgan Library, this folio was designed as the inauguration of the manuscript, setting the stage for the manuscript’s weaving of spiritual devotion, familial identity, and social status.

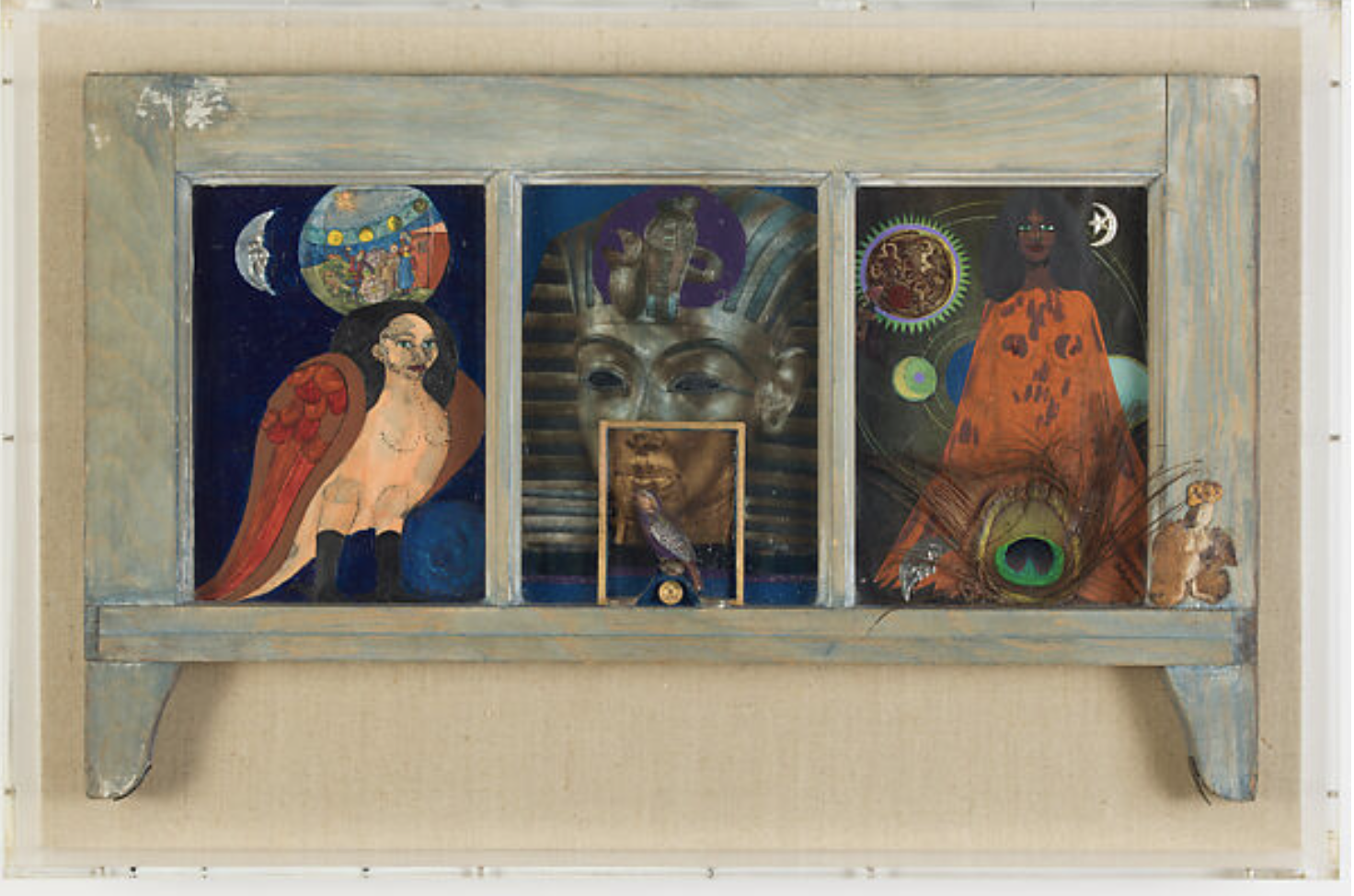

Saar’s Window of Ancient Sirens functions as an altar of a different kind. Constructed from a salvaged, teal paint-chipped, wooden window frame, the tripartite is populated with symbols of mysticism, worldview, and ancestral memory. The left panel features a red-winged siren figure beneath a crescent moon and a planetary orb, evoking both mythological themes and ancestral caution—she becomes a witnessing figure whose presence gestures toward resistance, representing the ongoing fight for Black female visibility in art history. The central pane exhibits an Egyptian funerary mask that speaks to ritual, mourning, and endurance across civilizations erased or misunderstood by colonial archives. At the fore of the mask lies a miniature frame where a small bird sculpture rests in front, recalling flight and fragility, but also observation—a quiet resolve to loss and transformation. Together, they create a symbolic image: the mask as body, the bird as spirit, the frame as portal. In the right panel, the Black woman dressed in orange takes a central presence, not as muse, but as keeper. She looks outward yet remains steady within the protective perimeter of the peacock feather, symbolic of spiritual vision and resurrection. The surrounding solar and planet-like figures reaffirm her power that transcends linear time, situating her as a force within both the ancestral past and imagined futures. Together, the three panels of Window of Ancient Sirens form a united visual cosmology, each distinct yet interdependent, showing how myth and memory shape cultural rituals and visions of the future.

Recent scholarship supports that Catherine was not a passive subject but an active commissioner of the manuscript’s imagery. Caroline Martelon argues that Catherine not only influenced the inclusion of her image but also helped shape the broader iconographic program, particularly where her natal symbols succeed those of her husband. Martelon emphasizes that this visual dominance stands in contrast to Catherine’s near invisibility in historical records, making the manuscript a crucial document of female agency and self-authorship. Furthermore, John Decker explains in his examination of the Hours’ marginalia, visual elements such as jewelry and heraldry were carefully embedded into the manuscript to signal alliances, blessings, and elite self-fashioning. Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child is not simply a space of personal piety, but a curated environment for self-authorship within a devotional system. Catherine’s presence on the page challenges historical notions of medieval female passivity. Her family crest displayed alongside sacred figures positions her as the curator in her spiritual archive, illustrating themes of agency and self-autonomy. Similarly, Saar also disrupts passive representation. Her figures do not recline or pose—they watch, stand, and assert presence. Their refusal to be simplified becomes a form of resistance. Through framing and symbolism, both works emulate curatorial imagination.

The symbolic density in both works reveals a shared desire to narrate spiritual presence through figures and forms. While Catherine draws on heraldry and biblical beasts, Saar pulls from cosmological and diasporic forms. The Morgan Library notes that the imagery in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves is “startlingly original,” populated with objects and figures that depart from biblical representation and instead engage in spiritual surrealism—beasts, hybrids, and an emphasis on personal insignia. Birds appear in both works as imperative symbolic figures, serving not solely as decorative elements but as carriers of spiritual and ancestral knowledge. In The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, the owl perched in the margin evokes themes of wisdom and divine watchfulness. At the same time, in Window of Ancient Sirens, the small sculpted bird speaks to fragility, soul flight, and the enduring presence of memory. These motifs point to a shared visual language in which birds embody guidance, observation, and transition. Additionally, the twisting vines in Catherine’s manuscript and the planetary shapes in Saar’s Window function similarly as border elements; they both extend the central figures into larger symbolic ecosystems, which blur the lines between ornament and belief. The merging of ancient symbols with planetary forms evokes a visionary Black identity, one that transcends time and spiritual frameworks. Giovanni Aloi frames Saar’s practice as a rejection of minimalist sterility in favor of what he calls a “re-enchanted cosmology,” allowing ordinary objects to become charged with spiritual potential. The dynamics between tradition and reimagination relate to Lisa Saltzman’s idea that memory in contemporary art is inherently partial and performative. Saar’s cosmology speaks from a place of survival, which is layered with grief, beauty, and power. Similarly to Catherine’s visual field, it is personal yet systemic, meant not only for remembrance but for resonance. These works study ideas of time and continuity– for example, the owl and the bird act as signs whose meaning exceeds their form. And as Baudrillard argues, entities operate within systems of signification, shaping meanings that exceed utility.

Lastly, both artists employ frames not as a border but as a portal, inviting the viewer to interpret sacred and personal meanings through visual cues. The manuscript’s miniature and the window’s wooden panes enclose space without limiting it. They arrange visual elements—like feathers, symbols, and figures—to guide the viewer’s understanding of the work’s personal and religious significance. As Susan Pearce notes, the act of assembling visual elements—devotional, ancestral, or imaginative—can reflect and actively construct identity. Catherine’s symbols reflect a desire for stability and salvation within her lineage; Saar’s collections demonstrate a longing to claim space within a lineage denied or fractured. Both frames work architecturally and symbolically, defining what is held within and how the viewer is invited to engage.

Each work functions as a space where identity and memory are visually constructed, preserving legacy and reshaping how we see ourselves in time’s continuum. Yet both works also remain relevant beyond their original periods. Each piece is rooted in its own devotional, social, and political framework while simultaneously pointing toward something broader, transcendent. Juxtaposing these two works reveals how spiritual art across eras reflects belief and actively shapes systems of power, visibility, and resistance. Their material choices, rich symbolism, and visual structures show how art can create new ways of preserving memory, imagining identity, and asserting cultural presence across material and cultural boundaries.

Annotated Bibliography

Aloi, Giovanni. “Betye Saar.” Esse 105, no. 105 (2022): 66–74.

In this critical article, art historian Giovanni Aloi examines Betye Saar’s assemblage practice with particular attention to its cosmological, diasporic, and spiritual dimensions. Aloi argues that Saar’s work forms a “re-enchanted cosmology,” wherein everyday materials possess sacred potential through ritualized curation. Though this piece does not focus directly on Window of Ancient Sirens, it offers a solid theoretical foundation for understanding Saar’s broader visual strategies. Deploying this text will allow me to analyze Saar’s work not as a nostalgic assemblage, but as a future-facing spiritual archive rooted in Afro-diasporic resistance.

Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. London: Verso, 2005.

This foundational philosophical text by Jean Baudrillard theorizes how material culture operates symbolically within modern consumer society. Baudrillard differentiates between the functional, symbolic, and signified roles of objects—arguing that objects are never neutral, but always participate in systems of meaning. While this book does not directly address either artwork, it will serve as a key theoretical lens through which I examine both Catherine’s illuminated manuscript and Saar’s assemblage. Baudrillard’s semiotic approach will enable me to decode the layered visual language of both works as functioning archives of belief, identity, and authorship.

Decker, John R. “Aid, Protection, and Social Alliance: The Role of Jewelry in the Margins of the Hours of Catherine of Cleves.” Renaissance Quarterly 71, no. 1 (2018): 33–76. https://doi.org/10.1086/696888.

In this peer-reviewed article, Decker examines the political and symbolic functions of jewelry and heraldic imagery in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves. He argues that these elements serve decorative purposes and assert alliances, protections, and social hierarchies embedded within elite devotional practices. This reading is essential to my writing because it frames the marginalia of Catherine’s manuscript as a performative space of self-authorship. Decker’s analysis supports my interpretation of the illuminated page as a curated environment where spiritual and political identities are visually negotiated.

Pearce, Susan M. On Collecting: An Investigation into Collecting in the European Tradition. London: Routledge, 1995.

Pearce’s work explores collecting as a deeply cultural and psychological act that shapes and reflects identity. She positions the collector not simply as a preserver of objects but as an active meaning-maker, whose choices form an archive of selfhood. Though her examples primarily deal with European cabinets of curiosity and museum practices, her theoretical framing directly informs my analysis of both Saar’s and Catherine’s works as forms of visual collection. Using Pearce’s framework, I can better analyze how each artist employs collected symbols to construct personal and sacred meaning.

Saltzman, Lisa. Making Memory Matter: Strategies of Remembrance in Contemporary Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

In this scholarly monograph, Lisa Saltzman explores how contemporary artists engage with historical memory through visual and material practices that resist fixed narrative. She emphasizes that when mediated through art, memory is often partial, performative, and layered. This text is beneficial in interpreting Betye Saar’s Window of Ancient Sirens as an affective archive that resists linear historicization. Saltzman’s theoretical insights will help me frame Saar’s cosmology as not merely personal or symbolic, but as a dynamic, future-facing construction of cultural remembrance.

Morgan Library & Museum. "Hours of the Virgin." The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. Accessed 2025. https://www.themorgan.org/collection/hours-of-catherine-of-cleves/58.

This institutional source provides curatorial analysis of the illuminated manuscript The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, specifically the folio depicting Catherine praying to the Virgin and Child. The Morgan Library notes the visual originality of the manuscript’s contents such as its inclusion of religious iconography and symbolism. Though this text is not a peer-reviewed scholarly text, it provides authoritative and visual historical context, enabling me to support my formal analysis and reinforce arguments on the manuscript’s role as a living archive of devotion and lineage.

Figures

Betye Saar. Window of Ancient Sirens. 1979. Mixed media assemblage in painted wooden window frame. 24 x 30 x 2 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Master of Catherine of Cleves. Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child. ca. 1440. Illuminated manuscript on parchment. Approx. 7 1/2 x 5 1/8 in. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, MS M.917/945, ff. 1v.

Betye Saar. Window of Ancient Sirens. 1979. Mixed media assemblage in painted wooden window frame. 24 x 30 x 2 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Master of Catherine of Cleves. Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child. ca. 1440. Illuminated manuscript on parchment. Approx. 7 1/2 x 5 1/8 in. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, MS M.917/945, ff. 1v.