Law & Social Change: Parsons NYC

Research Question: How do law enforcement crackdowns on counterfeit goods in Chinatown, NYC, shape vendors' livelihoods, identities, and resilience, and what does this say about the balance between intellectual property laws and social equity?

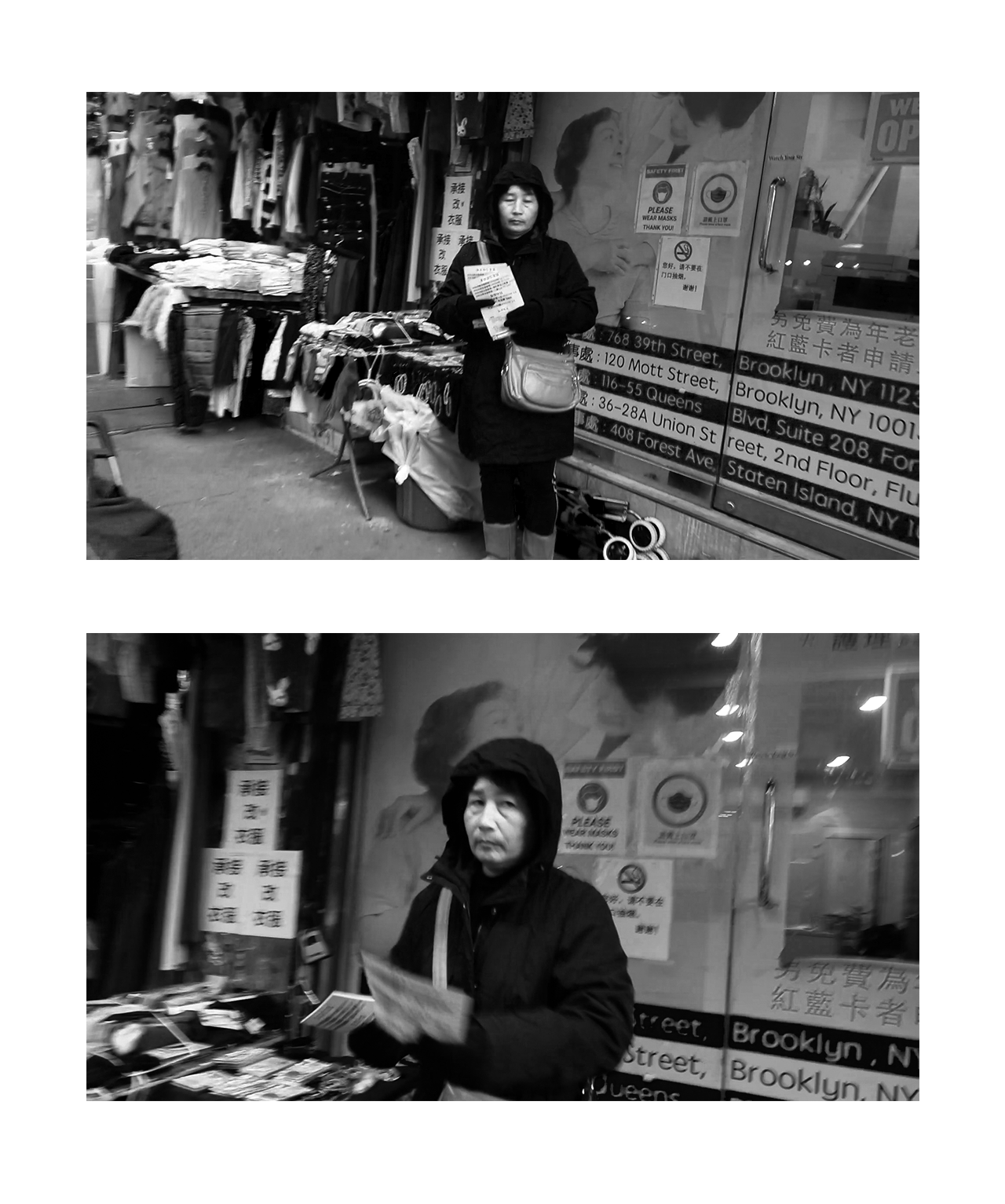

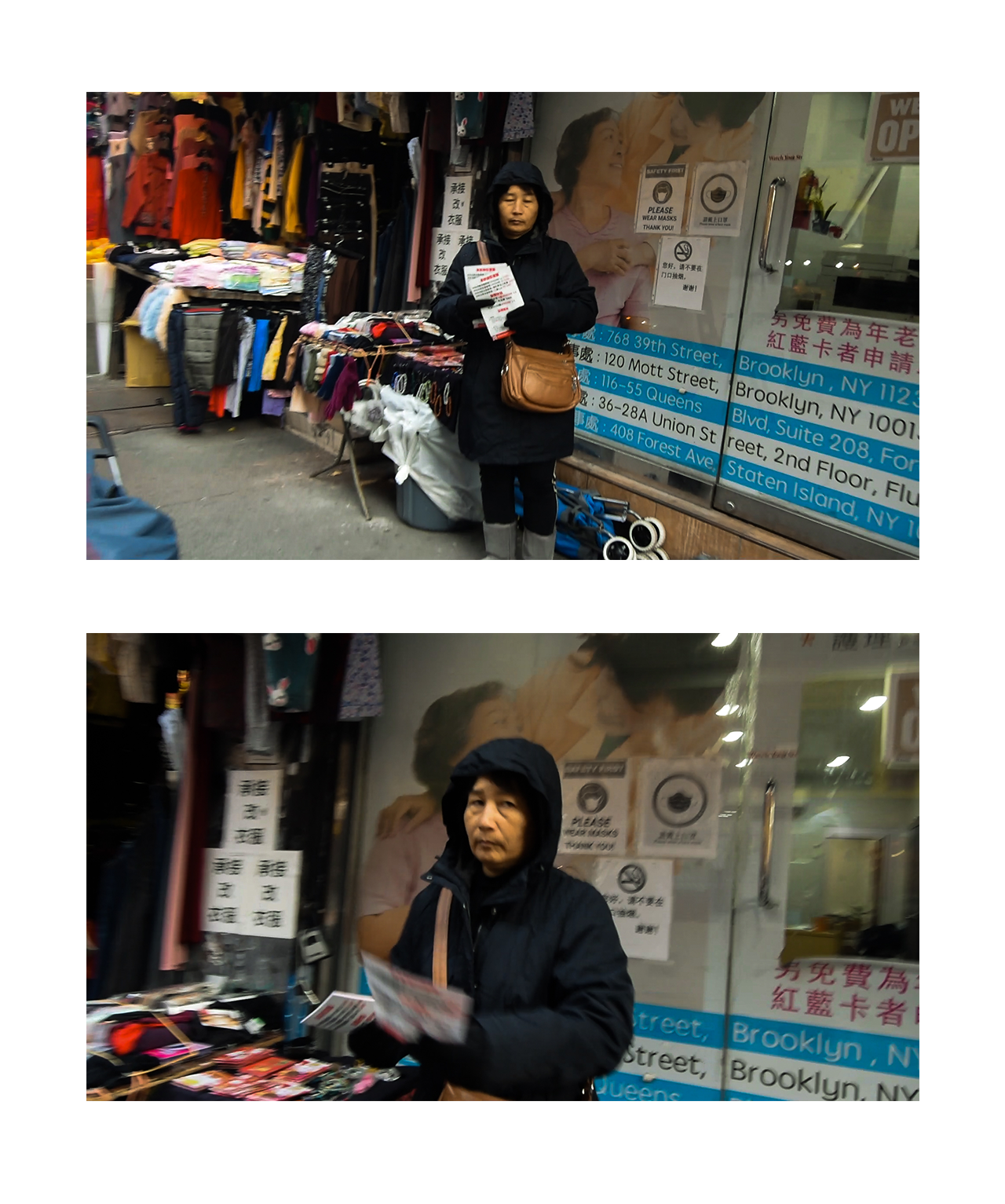

My project is a photojournalistic documentary series titled Counterfit Lives and the Chinatown Raids, which explores the human impact of these crackdowns on the vendors who survive within the shadows of NYC’s informal economy. By capturing their stories through portraiture, environmental shots, and counterfeit products, this series explores how intellectual property laws and enforcement policies intersect within the broader issues of economic vulnerability, immigration, and cultural identity.

My project lies within the larger legal and social framework of intellectual property (IP) enforcement and its consequences for marginalized communities. While IP laws are enforced to protect companies and promote creativity and innovation, their enforcement often disproportionately affects communities within society's margins. “Canal Street,” titled the street of counterfeit goods (though sales are not confined to the street itself), hosts an influx of vendors selling replica goods from handbags to technology. These vendors, many immigrants with minimal economic opportunity, navigate a precarious existence. Crackdowns on counterfeit goods aim to uphold corporate rights. However, they also disrupt the livelihoods of vendors, perpetuate cycles of poverty, and undermine cultural spheres like Chinatown, which are both economic and community hotspots.

Saskia Sassen and Keith Hart, scholars who have studied and discussed informal economies, argue that they are vital yet vulnerable components of urban life. They identify informal economies as spaces where people, excluded from formal systems, form their livelihoods even if those activities conflict with legal systems. Sassen builds on this idea by describing how regulatory systems fail to adapt to the realities of economic inequality, creating what she calls “regulatory fractures.” The sale of counterfeit luxury goods in Chinatown represents a “regulatory fracture.” Vendors are engaging in illegal activities as a survival strategy within the confines of an urban economy structured by rising costs and limited opportunity, not out of choice. Enforcement prioritizes safeguarding corporate IP rights, often ignoring the broader socioeconomic conditions like high employment rates, lack of affordable retail space, and barriers to formal entrepreneurship,p which drive individuals into informal, illicit work.

Counterfeit goods are a paradox in themselves. On the one hand, they undermine brand integrity and IP rights but also fulfill consumer demand for affordable alternatives in urban areas where inequality is more prevalent. In cracking down on counterfeit goods, law enforcement often targets the symptom rather than addressing the underlying conditions that catalyze their proliferation: economic precarity, lack of access to legal work, and systematic inequalities. The informal economy, defined by Keith Hart, encompasses income-generating activities outside formal regulatory systems. He highlights that informal economies often emerge as a response to the exclusionary nature of formal economy frameworks, illuminating the argument that informal economies are mere survival mechanisms for marginalized populations.

Similarly, Saskia Sassen argues that informal economies are not so-called “anomalies”; however, they are structured outcomes of advancing capitalism, reflecting the pressures of economic polarization and regulatory inadequacies. My project explores these perspectives: the paradox of Canal Street as both a thriving cultural hub and a site of legal precarity. My work also intersects with immigrant labor studies, more so how law enforcement policies criminalize survival strategies while ignoring the systematic barriers that force individuals and communities into informal economies.

The cultural impact of these raids shouldn’t be understated. Chinatown has a strong immigrant resilience and cultural exchange history, yet enforcement policies often strip away its vibrancy. The marketplaces that shape Chinatown, with their eclectic mix of goods and emotional energy, reflect its community's diversity, creativity, and entrepreneurial spirit. However, enforcement policies often disrupt this by replacing its sense of belonging and cultural pride with fear and transience. By highlighting vendors' experiences, this work highlights the need for more equitable approaches to protect vulnerable workers while respecting the cultural significance of spaces like Chinatown.

When taking the photos for this project, I encountered vendors who were deeply cautious about being documented. Many vendors explicitly stated “no photos,” quickly taking action by hiding products, fleeing the screen, or attempting to cover the camera. The environment felt tense and anxious, almost as if the vendors were always on edge, ready to pack up their products and move quickly. The transient nature of their jobs was quite striking: hidden stalls, quick exchanges, long walks to hidden shops, makeshift displays that could be dismantled in seconds. The vendors’ readiness to evade enforcement demonstrated the intensity of law enforcement in the neighborhood and the structural vulnerabilities that push them into such a precarious lifestyle. These interactions underscore how policies designed to protect intellectual property often criminalize the livelihoods of individuals with few alternatives.

My project critiques the enforcement of IP laws as emblematic of broader inequalities in legal frameworks and their effect on informal economies. By criminalizing these vendors, these policies exacerbate economic precarity without addressing systematic conditions like income inequality and accessibility to formal markets, which drive individuals into informal workplaces. While protecting intellectual property is essential, focusing on raids and crackdowns fails to address the structural issues driving informal economies. Sassen’s argument demonstrates that policymakers should move beyond criminalization to develop new regulations recognizing how integral informal economies are to urban life. For example, policymakers could integrate a licensing reform, and decriminalization could provide gateways for vendors to operate legally while preserving their livelihoods.

Counterfeit Lives in Chinatown invites viewers to reflect on the role of law in perpetuating or alleviating inequalities. My project aims to reframe the narrative around Chinatown from illegality to resilience, illuminating the community's contribution to New York City's identity and its deservingness to be supported and not criminalized. By documenting the living realities and narratives of Canal Street Vendors, my project seeks to humanize a criminalized population while challenging audiences to reconsider the dynamics between corporate protection and social equity in forming a just society.

Bibliography

Hart, Keith. "The Informal Economy." Cambridge Anthropology 10, no. 2 (1985): 54–68.

Daza-Caicedo, Sergio, and Edgar Ramírez. "The Informal Economy: Between New Developments and Old Regulations." Journal of Economic Issues 54, no. 2 (2020): 565–74.